What is happiness to you?

Defining happiness is not easy, and nor should it be. What makes one person happy is another person’s nightmare. I can’t imagine feeling happy going to a football match, but for many people, it’s a weekly pilgrimage. Similarly, my idea of happiness (sitting on the sofa in the quiet with a book) no doubt sounds hellish to plenty of people.

What we can say is that happiness is something we feel in our bodies. It’s a positive emotion that is associated with chemicals such as serotonin, oxytocin, dopamine and other endorphins.

But how are brands taking this emotion, a very personal, intimate emotion we feel (quite literally inside ourselves) and turning it into a facet of capitalist agendas?

Brands Selling Happiness

These are just three examples of brands using our emotions to sell us things.

- McDonalds – I’m Lovin’ It

- Wagamama – From Bowl to Soul

- Costa Coffee – A Little Cup of Happiness

We know that none of these things will bring us actual happiness, love, or spiritual nourishment, yet we are happy to believe in it.

Why?

Because the products themselves make us feel good for the moment of consumption. We absorb the ‘feel good’ and align it with the brand messaging by association.

Brands everywhere, all the time, are selling our emotions back to us. Fear of missing out, fear of not being included, but also the idea that everyone else is part of it and you aren’t. By not participating in X product or service, you’re the one left on the sidelines, the one missing out on these great experiences and emotions – and who doesn’t want to feel happy and included?

By commodifying emotion (and therefore the emotional response we crave from our brains) into the form of an object, it becomes an attainable thing. We’ve all heard ‘money can’t buy you happiness’. But perhaps it can buy you a sense of being included in society, maybe even one of security?

Can a brand feel the love?

Think about your intention when you say ‘I Love You’ to someone – especially the first time you say it in a relationship. You don’t throw that phrase around carelessly. We understand that love is a deep and powerful emotion not to be trivialised. Telling someone you love them is a very intimate exchange and one that can lead to great reward – or great heartbreak.

It’s the same with the idea of the soul. For those with religious beliefs, the soul is potentially the most important part of a person. It is something to be cherished and shared only with those closest to us. We talk about the idea of ‘soulmates’ as being an incredible, meaningful relationship between two people.

Is ramen really the conduit to your soul? Does coffee really bring you true happiness?

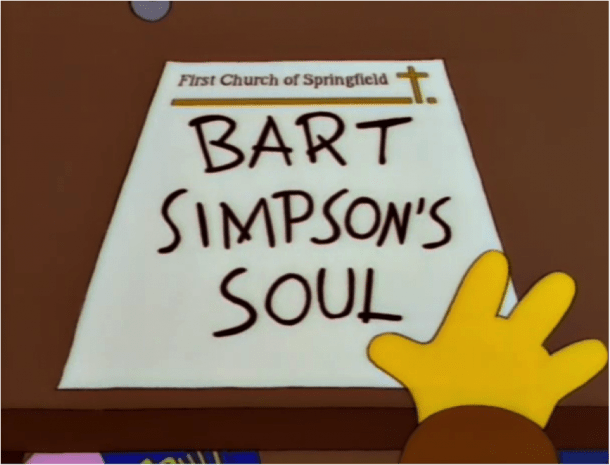

If you’re familiar with The Simpsons, you’ll know the classic episode “Bart Sells His Soul”, where Bart sells his soul to Milhouse for $5, claiming he doesn’t believe in it. Throughout the episode, however, he starts to feel the ramifications of selling his soul after strange events happen to him. He feels like a part of himself is lost and scrambles to get the piece of paper on which he signed his soul away back. On getting it back, he eats the paper, therefore reclaiming his ‘soul’.

Bart’s dabble with capitalism here in selling his soul for a monetary value shows that the way we feel cannot have a price. Whether he did or didn’t have a soul to sell doesn’t matter – what matters to him in the end is the idea that he has a soul, and the emotional fulfilment that comes from it. His sister Lisa is the one who returns his soul free of charge to him, therefore removing any kind of capitalist intent.

However, brands have no issue tossing out the idea of love, souls, or happiness. In fact, the more ways they can find to tap into those different ideas of love/happiness/fulfilment, the more people they can reach and get them to buy things. And even better, the deeper the meaning they can get us as consumers to ascribe to it, the better. Big ideas such as love, inclusion/security, and even fear or hatred are all regularly used in advertising and marketing. They speak to an innate part of us as consumers that we understand, and we want it!

Emotions and objects.

I realise this sounds really cynical and jaded. While it can be a bit depressing to realise our basic emotional responses are being manipulated in order to make a sale, having worked for many brands and on advertising campaigns, they’re not all heartless monsters after money. A lot of them really do care about having a good product or service that makes things better or easier for people. If anything, more and more brands are aiming for an authentic approach that isn’t hiding behind the smoke and mirrors of marketing.

So we know brands are trying to sell us emotions, and the more successful ones are convincing us. Selling those emotions is attached via objects or services.

But when you see an object out of context, it’s hard to ascribe emotional rationale to it. We often talk about objects in quite personal terms ‘I love that car’ ‘I hate those shoes’ etc. You can have a snap judgement of something but you likely don’t give it much thought or emotional investment.

You’re also probably familiar with the idea of emotional or sentimental value. We often see this as being of no value – as in it’s not worth anything monetarily in exchange. However, with enough experiences, or with enough marketing, it’s possible to ascribe emotional value to an object – and for that object to have an emotional impact on us.

This can even go so far as to create demand – people want the object because we believe/know it will create the desired emotional effect. Luxury brands are exceptionally good at this, generating demand through perceived emotional gain (as well as the objects acting as symbols of wealth, status and power). Porsche has ‘There is no substitute’. De Beers has the famous ‘A Diamond is Forever’, and Valentino has ‘Beauty is about eternity.’ All of these brands have absolutely loaded these slogans with emotional intent, which is half the battle with establishing a luxury brand voice.

So objects make us want them through messaging. Emotions make us want objects through response. How do we connect the two?

Connecting to objects.

Touch is a fascinating sense largely because we use it so often and consider it so little. We tend to think of it as being confined to the hands, but in reality your skin, the largest organ in your body, is your sensory boundary that allows you to interact with the world. We also often have shared emotional/objective experiences. Whether that’s a comfortable bed, a hot bath, a pinching pair of shoes, or a paper cut, all of these are touch-based interactions that we come to know through our skin.

- Think about the chair you’re sitting on, how you’re standing, the clothes on your skin. We’re constantly touching and interacting with objects around us through touch.

- Touch also powerfully links to our emotions, creating happy/comfort or irritated/discomfort reactions.

- Our bodies are the way in which we interact with the world, using our senses and emotions.

- Bodies exist both individually (contained within the skin) and as part of a wider collective (families, partnerships, even crowds). Bodies can be added to, and taken away from – they are in a state of constant flux, much like emotions.

- Adding to the body might be food, drink, sleep, medication, tattoos or piercings. Taking away from the body might be tears, vomit, blood, or exhaustion. In an emotional sense, it might be happiness or fear that is added/removed.

- We use our senses and bodies to determine our emotional reactions to the world around us – good or bad! We also use them to interact with objects, also for good or for bad.

This is known as affect, and it helps us understand the world around us through our bodies, objects, and emotional/behavioural responses.

Affect theory definition

- The idea that feelings and emotions are the primary motives for human behaviour, with people desiring to maximise their positive feelings and minimise their negative ones.

- ‘Emotions are not simply “within” or “without” but that they create the very effect of the surfaces or boundaries of bodies and worlds’ (Sara Ahmed, 2004: 117)

- We also have ‘sticky affects’ – emotions become ‘stuck’ to objects through association. They collect emotions around them. You might see this in effect at something like Ground Zero, childhood toys, or family heirlooms. Sticky affects can be positive or negative associations.

How do we connect emotions to objects?

Marx believed in connecting to the material, and rooting within materials – objects, economy etc. New materialism theory incorporates new ways of thinking, moving past the individual and instead into how they can work together, including at an ideological level.

Emotions move from inside-outside and outside-inside (i.e. object to body, body to object). This is where we project emotions out and onto objects, and objects can project onto and into us with their perceived emotional value.

With this, we get so ‘stuck’ on the idea of happiness, and the idea that objects can help us attain it, we become stuck in a cycle known as ‘cruel optimism’. Lauren Berlant wrote about cruel optimism in her 2011 book, citing:

“All attachments are optimistic. When we talk about an object of desire, we are really talking about a cluster of promises we want someone or something to make to us and make possible for us. This cluster of promises could seem embedded in a person, a thing, an institution, a text, a norm, a bunch of cells, smells, a good idea—whatever.” (page 23).

Even more so than cruel optimism is the idea of cold intimacies. Eva Illouz‘s work on this is outstanding, noting that we have commodified our private, emotional selves via capitalism. “Emotional capitalism is a culture in which emotional and economic discourses and practices mutually shape each other,” (2007: 5). The more we crave an emotion, the more the market will rise to meet that demand.

You can’t force someone to feel a certain way emotionally – but you can persuade them to want an object by playing on their emotions and senses. In the game of capitalism, especially as we lean more into selling the idea/experience/emotion of something rather than the thing itself, we are sure to see more brands become entangled with the idea of emotions and the good life.